HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE INTERNMENT CAMPS

“We have no one to go to for help. Not even a church. Anything goes, now that our President Roosevelt signed the order to get rid of us. How can he do this to his own citizens? No lawyer has the courage to defend us. Caucasian friends stay away for fear of being labeled "Jap lovers." There's not a more lonely feeling than to be banished by my own country. There's no place to go.”

—Kiyo Sato

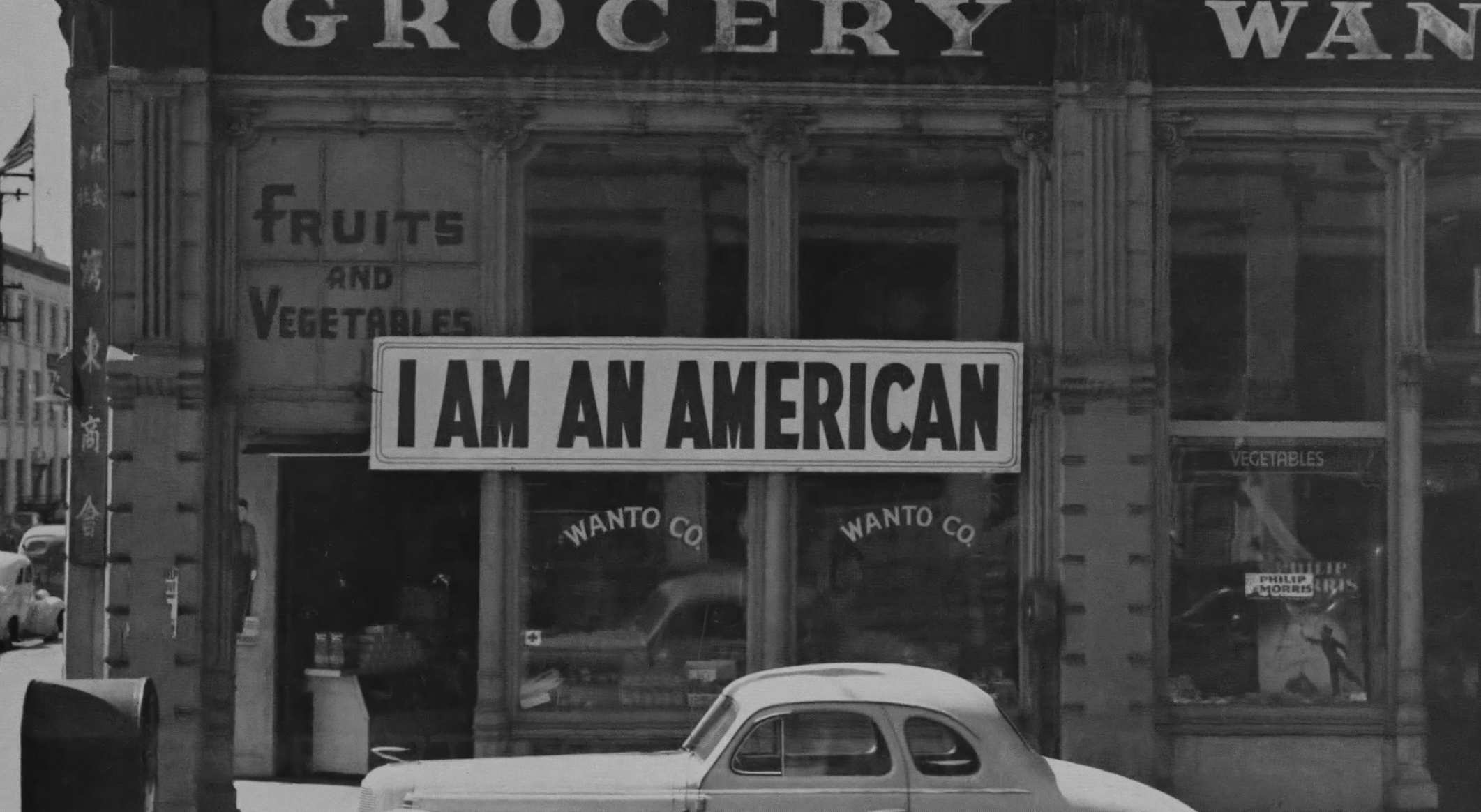

Japanese internment camps were established during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066. From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, would be incarcerated in isolated camps. Enacted in reaction to the Pearl Harbor attacks and the ensuing war, the incarceration of Japanese Americans is considered one of the most atrocious violations of American civil rights in the 20th century.

Executive Order 9066 affected the lives about 120,000 people—the majority of whom were American citizens.

10 Internment Camps

General John DeWitt of the Western Defense Command advocated for detaining the Japanese population and placing them in military zones to be monitored so that another Pearl Harbor could supposedly be avoided. The War Relocation Authority was set up to organize the detainment of 120,000 Japanese American in ten camps in remote areas of the US, primarily on tribal land.

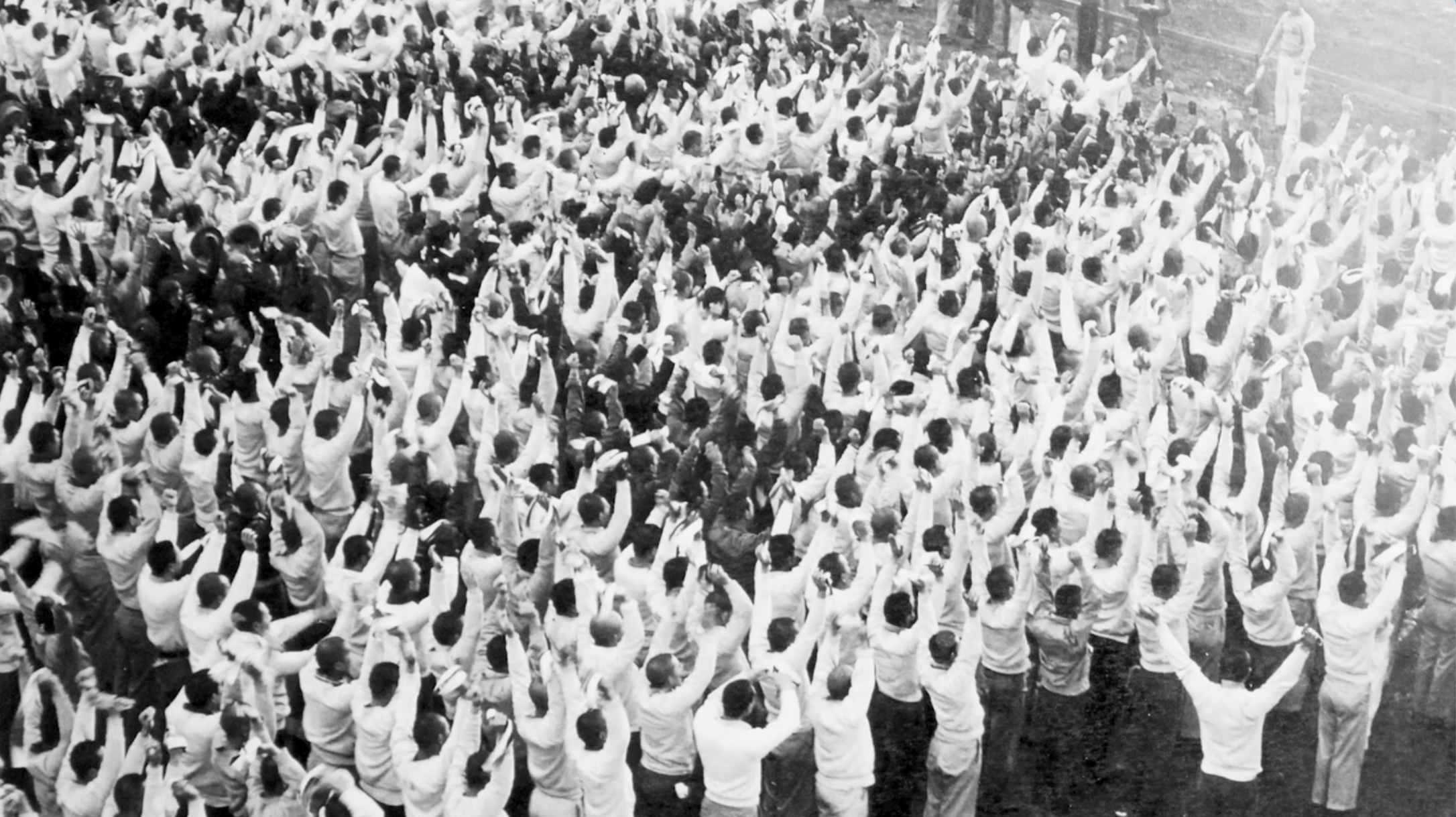

In 1943, a resettlement program was started so that Japanese inmates could leave the system if they signed a registration form and passed an FBI check. The registration form came to be known as the loyalty questionnaire and sparked protests in all ten camps. Two questions asked inmates to volunteer for combat duty and forswear their allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Of the 15% who refused to answer the questionnaire or said no to either of the questions, 12,000 who resisted became known as the “No-No’s” and were taken to the Tule Lake internment camp, which had been converted to a maximum security segregation center.

Anti-Japanese Sentiment and Racism BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR

Amid racism, paranoia, and fears of sabotage, people labelled Japanese Americans as a danger and potential traitors. The FBI conducted searches, took belongings, arrested community leaders.

After the war ended and the incarcarees returned home, many were subjects to post-war racism and faced discrimination and resentment

Camp conditions were bad with overcrowding, curfews, unwarranted searches, restriction of work and recreational activities, and imprisonment of “troublemakers” in stockades

The Hoshi-Dan

Angry young men joined the “Hoshi-Dan”, a militaristic nationalist group aimed at preparing its members for a new life in Japan which ran military drills, protested against the WRA, and were against sympathizers.

The Renunciant Act of July 1944

When the Renunciation Act was passed in July 1944 to encourage Japanese American to renounce their citizenship and be deported to Japan, 5,589 people (over 97 percent of them Tule Lake inmates) expressed their resentment by giving up their U.S. citizenship and applying for "repatriation" to Japan.

All the camps were closed at the end of 1945, except for Tule Lake’s “renunciants” who were going to be deported back to Japan. Most of the renunciants, over 4,262, regretted their decision to renounce their U.S. citizenship and petitioned to stay in the U.S.

CAMPS CLOSED

The War ended on September 2, 1945. Tule Lake was officially closed in March 20, 1946 after the petitions were resolved. People were kicked out of the camps and given $25 and a train ticket to their pre-war address even though many had no homes or a job to go back to.

APOLOGIES AND REPARATIONS

President Gerald Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066 in 1976, and in 1988, Congress issued a formal apology and passed the Civil Liberties Act awarding $20,000 each to over 80,000 Japanese Americans as reparations for their treatment.

STIGMA AND SILENCE

Japanese-Americans who were returning home faced discrimination and prejudice from the civilian population. The No-Nos were also subject to stigma within the Japanese American community and often kept silent about their history.

Resources

Densho Non-Profit Organization documenting Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII

“War Did Not Break This Family”: Nancy Kyoko Oda and the Tule Lake Stockade Diary

Ansel Adam’s Photograph Collection of Japanese-Americans at Manzanar

TedEd - Ugly History: Japanese American incarceration camps - Densho

History - Japanese Internment Camps

National Archives - Japanese-American Incarceration During World War II